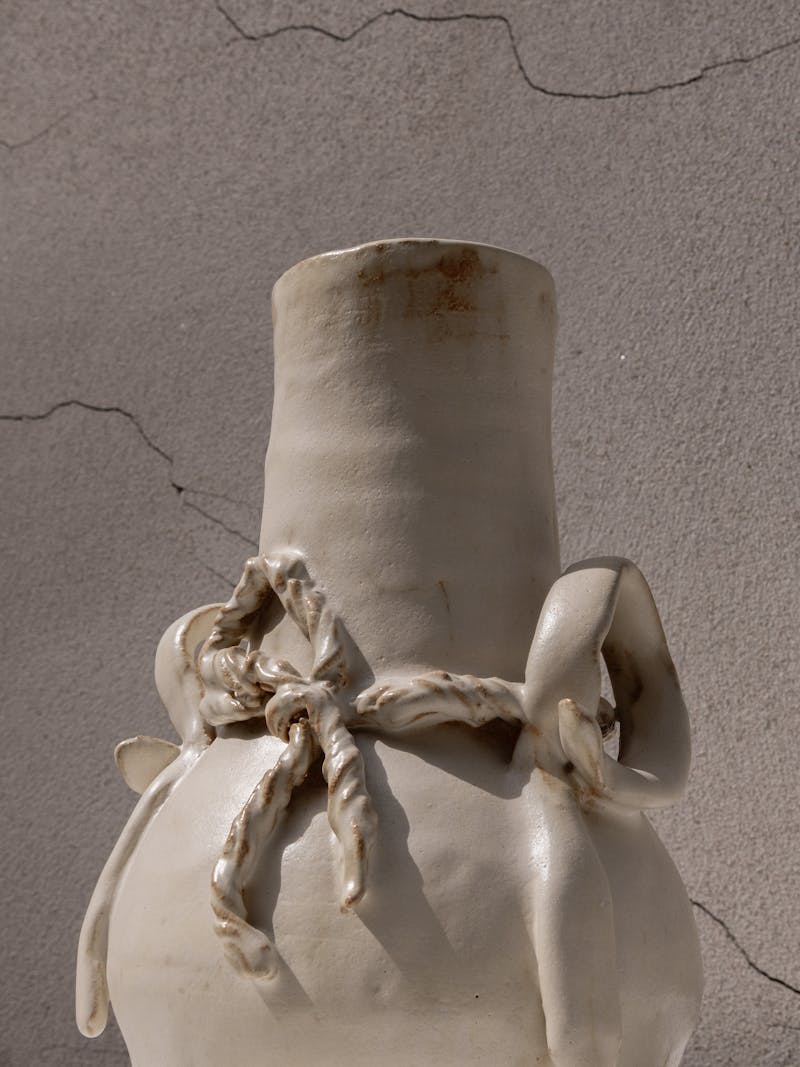

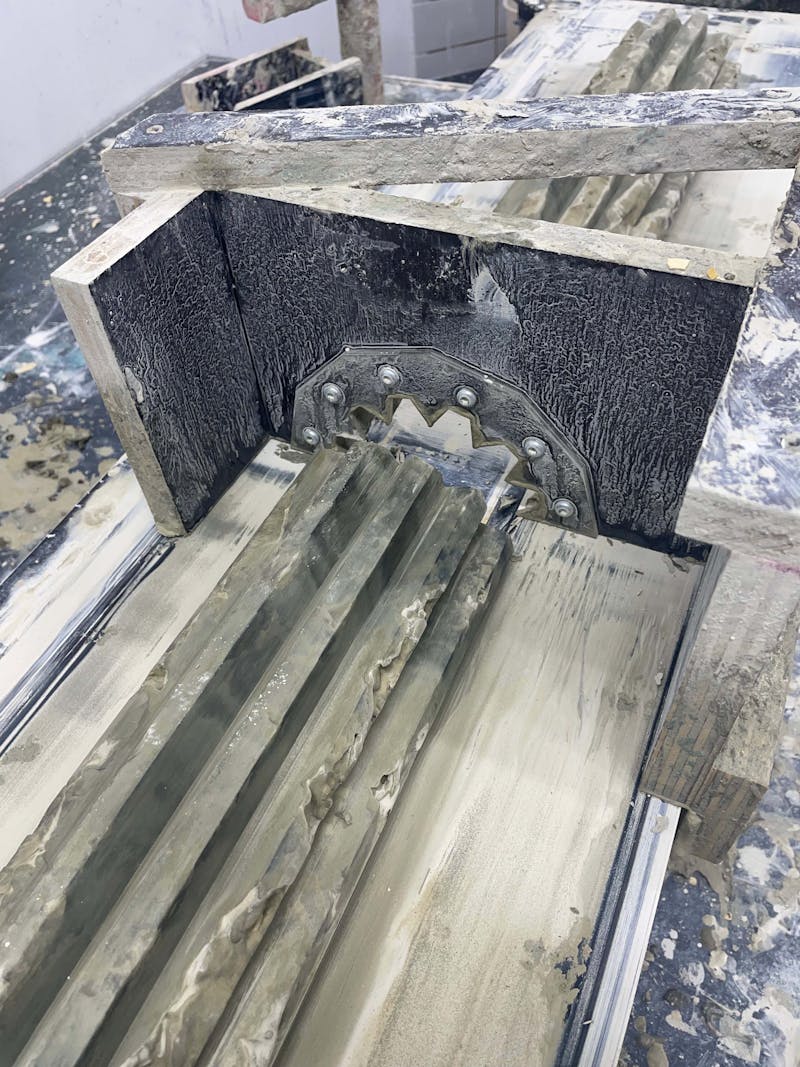

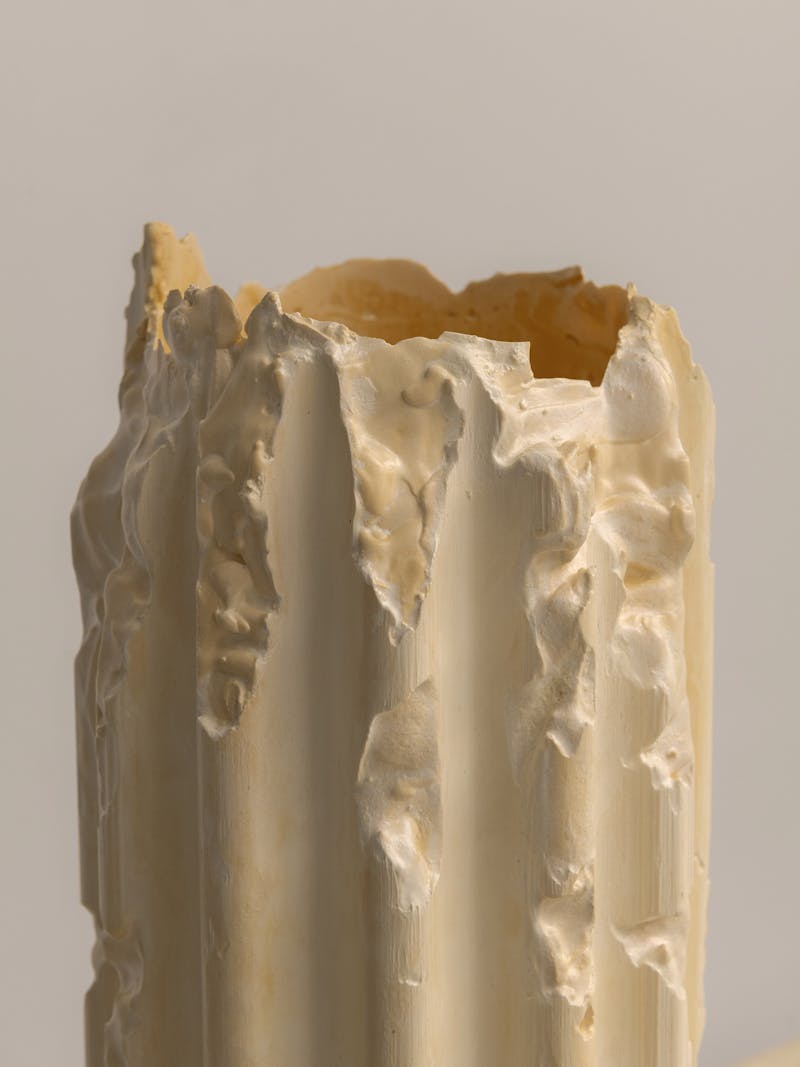

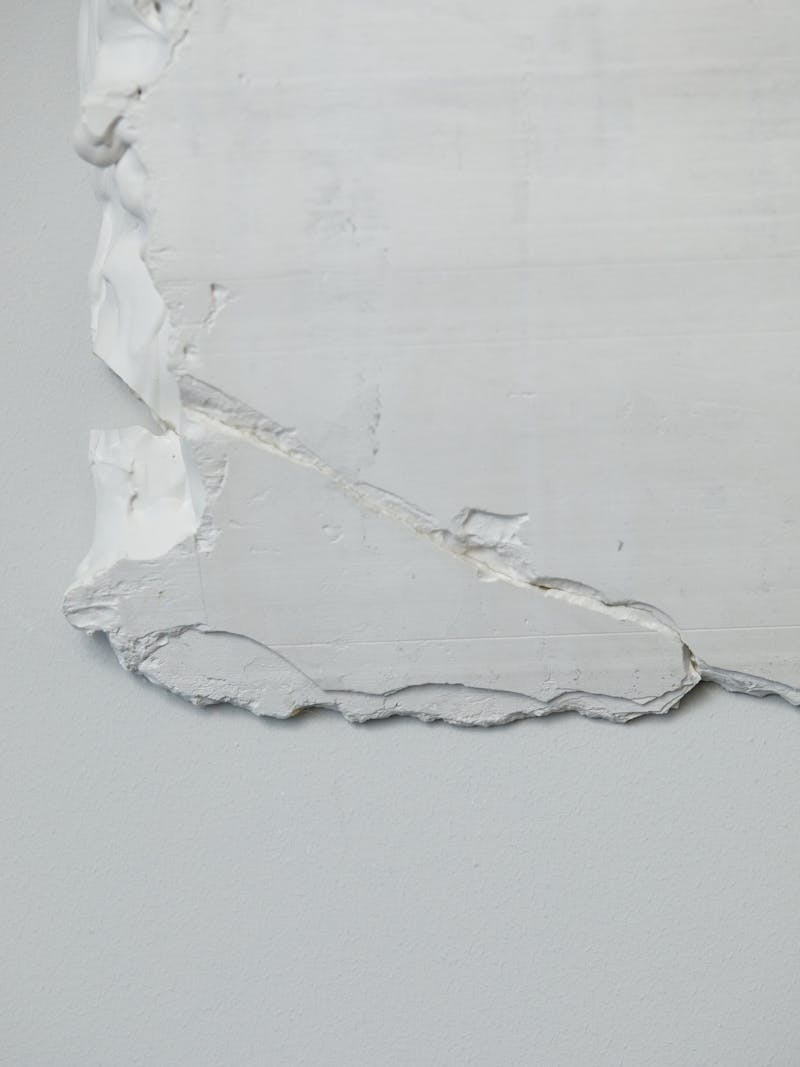

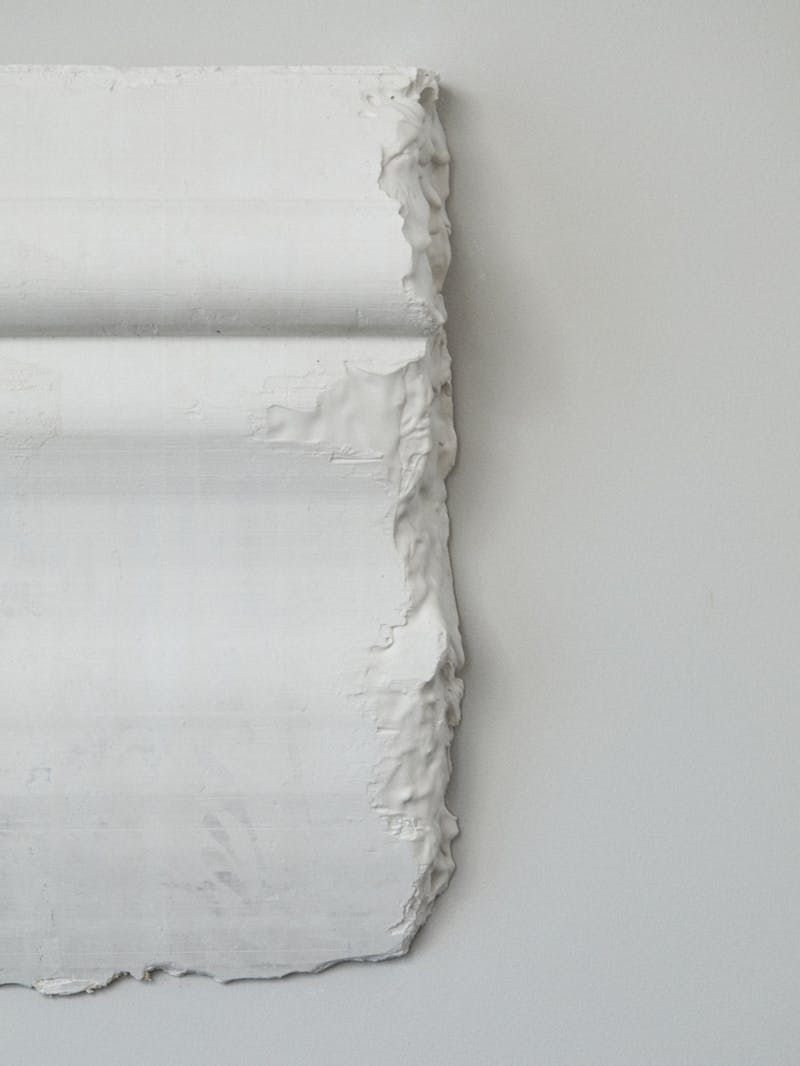

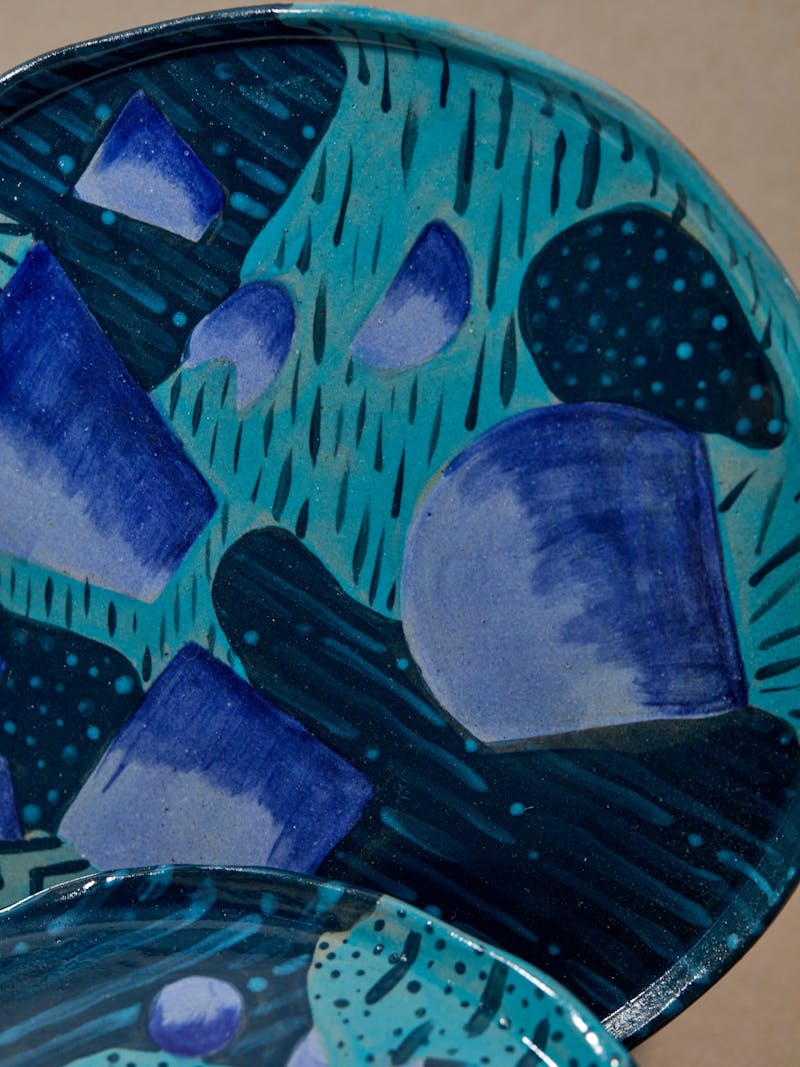

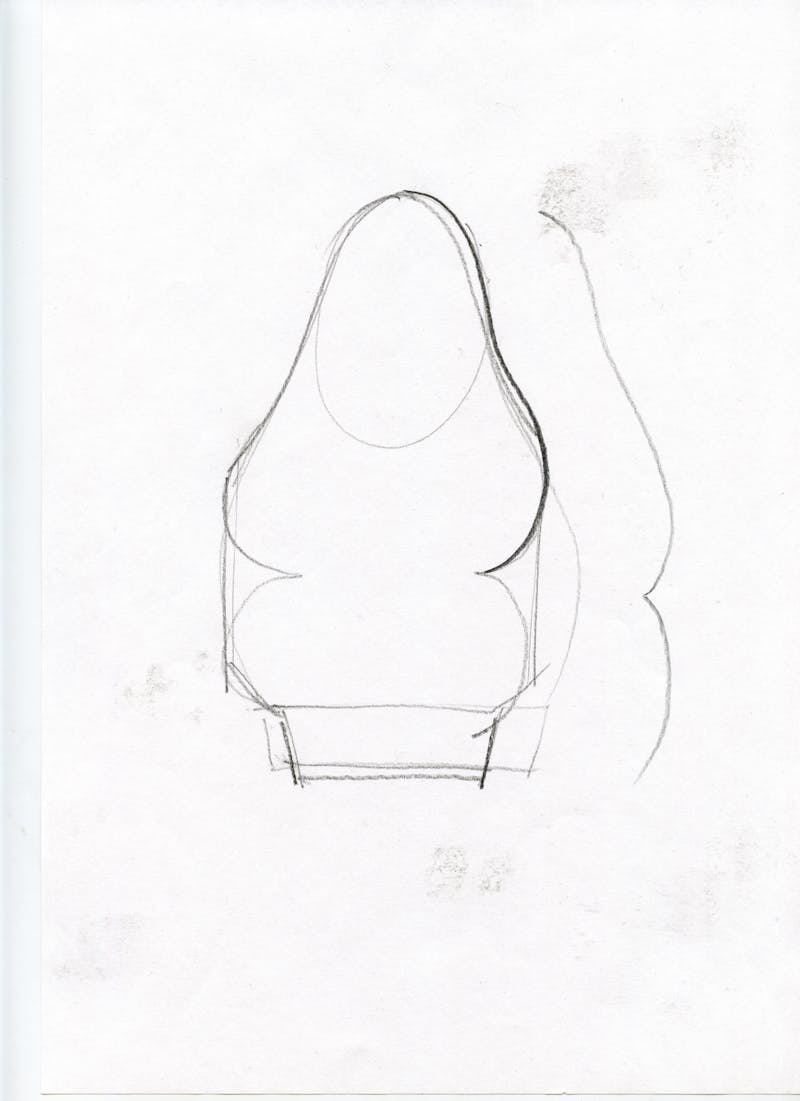

For the new spring collection “Observations” by Metamorphoses Objects, Rotterdam-based designer Lenny Stöpp has crafted a collection of beautiful Cornice Vessels and Twirl Bowls. Recently, we visited him in his studio to chat about his ‘Cornice’ project. We delved into his creative process, sources of inspiration, future aspirations, and the importance of observation in the journey of getting to know his material — literally and figuratively. His special ‘Cornice’ series emerged as a graduation project in 2019; Lenny, however, was deeply intrigued by the techniques he learned under the guidance of a mentor at the academy, spurring a dedicated commitment to his craft. Now – four years later – the project continues to evolve and his authentic pieces can be found across the globe.